Cocaine was many a comic's milk during the early-1980s. Several stand-ups I knew or partied with preferred the powder to just about anything else, booze included. I stuck my nose in a few times. Blow was never really my speed, which left me out of many conversations and frenzied back-and-forths.

Being a pothead writer in a roomful of snorting, sniffling comedians put me in another space altogether. While I waxed conceptual, the others were grinding their teeth, zipping from bit to bit, skimming the surface of their minds before pushing their faces against mirrors, glass tables, and in one case, a dirty tile floor.

I thought back to those coked-out times while watching "SNL: The Complete Fourth Season." It was the original SNL's most famous year, 1978-79, a season where comedy was rock and roll, drug humor at its peak, cocaine the main engine. I don't know if another American comedy show ever referenced coke use the way SNL did that year. You certainly wouldn't see that now, which dates these episodes in a weird nostalgic way.

When researching Michael O'Donoghue's biography, many of the writers I interviewed told the same stories about blow in the SNL offices; how it fueled them on Tuesday nights as they shaped scripts for the Wednesday read-through; how the show's hotness guaranteed a steady supply of coke, and so on. You definitely see the results in this seven DVD set.

Some of the humor is cheap. Much of it is inspired, though a certain meanness comes through. When you watch these shows in bulk, comic aggression is immediate. Little wonder that Tina Fey says she would've been frightened to work on the original SNL. It wasn't for the faint-hearted.

While the fourth season featured fan favorites like The Nerds, The Samurai, and The Coneheads, there was an abundance of strange, subtle, conceptual humor as well. John Belushi and Gilda Radner were the most popular faces onscreen, their entrances eliciting applause and yells, but the rest of the cast did solid work, the ensemble's chemistry so tight that it seemed nonexistent.

The writers are heavy as extras and bit players, and they too blend in nicely. It was a moment when fame and satire uneasily coexisted, though it was clear which way SNL would ultimately go. When a program generates the ratings and revenue that SNL did that year, satire is inevitably bled dry, or left to find its own way home. It's hard to attack the system when your brand is all over the media. Still, given corporate reality, SNL's fourth season delivered its share of hard hits, some of which made the audience gasp or groan, depending how tasteless a joke was perceived. As O'Donoghue put it, making people laugh is the lowest form of comedy.

The most popular player that season was also the biggest distraction. Coming off the enormous success of "Animal House," and riding high with The Blues Brothers, John Belushi had bigger things in mind other than SNL. There are scenes where Belushi simply phones it in, his casual, indifferent approach a huge contrast to his earlier, more focused work. Belushi's star was getting brighter. His celebrity overshadowed the show, something the writers played with and Belushi made mild fun of, but clearly his foot was out the door.

When Kate Jackson of "Charlie's Angels" hosted, Belushi, spent from partying, sweated profusely, his voice gravelly, his timing shot. When Richard Benjamin hosted, Belushi didn't show up at all. He claimed to have an ear infection and remained in LA. Occasionally through the fourth year, Belushi nailed a character or scene, employing some of his old magic. But Belushi the Legend was taking over, driving him to his final destination.

In contrast, Gilda Radner performed at an inspired level, her comedic gifts shining in sketch after sketch. She remains perhaps the most natural cast member SNL ever featured (along with Eddie Murphy), and no matter the material or character, Gilda made it work and work well. There's a warm energy to her performances, even when she played Candy Slice, the drunk, drugged out punk singer based loosely on Patti Smith.

Candy Slice is rude, obnoxious, barely cogent, yet in Gilda's hands, she's also vulnerable and somewhat sweet. It's as if Judy Miller, Gilda's energetic little girl character, grew up to become queen of CBGB. Gilda threw herself physically into Candy's music, an uncompromised energy that mined both parody and rock. She suffered from bulimia during this period, her body rail thin, but Gilda's power demolished such restrictions. She could smash through a wall if she willed it.

This season was also Bill Murray's coming out party. Having struggled in his early SNL days, Murray attained his comic balance through the third season, and by the fourth year, he moved to the show's upper tier. Like Gilda, Murray made his work seem effortless, though his energy was decidedly odder, at times potentially explosive.

His lounge singer Nick is the best example of this, as he aggressively entertained whatever small room would have him and his accompanist on piano, Paul Shaffer. As Nick, Murray runs high to low, soft to loud, and there's never a false or clumsy transition from one mood to the next. Plus, no one butchered a song quite as well as Nick, though his commitment to the material is sincere.

The rest of the cast kept a steady beat. Jane Curtin and Dan Aykroyd remained as precise as ever (though Aykroyd was moving away from his conceptual roots toward a broader comic persona). Laraine Newman's chameleon mode of comedy was still strong, despite her seemingly brittle appearance. But perhaps the biggest surprise is Garrett Morris.

Often dismissed or overlooked in SNL retrospectives, Morris delivered a number of fine performances during this season. From a smooth-talking convict locked in a family's hall closet, to a stuttering singer in a production of "Porky and Bess," to his most famous character (developed with Brian Doyle-Murray), Chico Escuela, the Dominican baseball player-turned-announcer, Morris held his own on such contested turf. On the Walter Matthau show, Morris beautifully sings Mozart. He doesn't get the love he deserves, but Garrett Morris had some serious chops. Trouble was, he had to take what he could get among more celebrated talents.

The writing was eclectic and individualized, something you don't see on SNL anymore. In the original years, geeks like me could tell which writer conceived which bit. Lorne Michaels drew upon diverse voices to give the show a unique flavor.

Jim Downey's "What If?" (what if Eleanor Roosevelt could fly? what if Superman grew up in Nazi Germany?) shared time with Tom Schiller's "Bad" productions and original films. Anne Beatts and Rosie Shuster not only worked on The Nerds, they turned Buck Henry into Uncle Roy, a middle-aged pedophile babysitter who channeled his desires through "childhood" games like Invisible Leg Doctor and Undress Dolly with a Vacuum Cleaner. Walter Williams pumped out numerous Mr. Bill shorts.

But perhaps the best-known writers that year were Al Franken and Tom Davis, who regularly appeared in their own show-within-a-show. These bits are often very funny, if sometimes harsh, a razor wire Bob and Ray.

A couple of times, Franken and Davis announce that they are communist revolutionaries working to overthrow the US government. In one bit, they illustrate bourgeois political corruption, ending in assassination; in another, they try to undermine our imperialist culture by using massage-oriented porn. Each of these scenes are sponsored by the Communist Party -- "The Shah's Not

Our Friend" -- complete with large hammer and sickle. Of all the things Norm Coleman could've used against Al Franken in the Minnesota Senate race, I'm surprised he didn't put these images in a commercial. Oh sure, Franken would say it was satire, but was it really . . .?

For me, the most inspired, original writing in the fourth season came from Don Novello and Brian McConnachie. Novello was best known as Father Guido Sarducci, the Vatican gossip columnist, whose absurdist takes on the Catholic Church still resonate. But Novello also authored two running, slice-of-life sketches: Olympia Cafe and Scotch Boutique. The former was more popular, its "cheeseburger, cheeseburger, no Coke, Pepsi" becoming a national catchphrase. Yet despite that covering, the Olympia Cafe pieces were subtly acted, Novello's attention to detail well defined.

Scotch Boutique displayed even more precision. A store that sells only scotch tape opens in a dying mall. At first seen as a ridiculous idea, the Boutique soon prospers, selling tape to the other store owners so they can put up their Going Out of Business signs. These pieces ran through the entire season, forming an extended narrative as opposed to recurring one-liners and character turns. Scotch Boutique was an intelligent look at people confronting failure and loss. There were no jokes, only situations, each more dire than the last. Those pieces are perhaps the most poignant work to ever air on SNL.

Brian McConnachie's work defies easy definition. A National Lampoon vet, McConnachie established himself quickly on SNL, writing ethereal bits that sometimes confused other staffers, Lorne Michaels included.

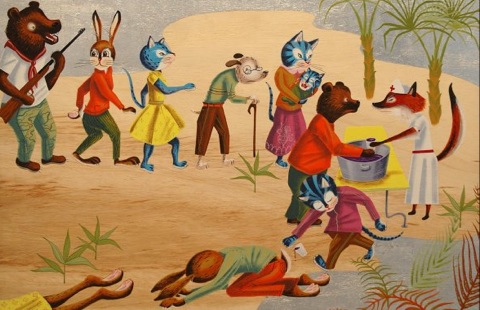

In "Name The Bats," two game show contestants are locked inside a barn where they must give the bats swooping down on them proper names -- not based on their species, but actual human names. But the contestants are so traumatized by the bat assault they can barely breathe.

In "The Spirits of Christmas," an alcoholic is visited on Christmas Eve by three animated figures from booze bottles who take human form. They teach him the true meaning of the holidays: getting so drunk that you can't find your ass with both hands. It's a somber little piece, with Elliott Gould as the boozer.

In "Cochise At Oxford," the Apache leader enrolls at the august English university, maintaining a stony silence as the professor, played by Eric Idle, gives a bizarre lecture about Thomas Hardy's furniture inflating and expanding, sending Hardy running out of his house in fear.

McConnachie was invited back for SNL's fifth season, but declined, citing the nasty, coke-fueled atmosphere in the offices. He later joined "SCTV," where he won a writing Emmy.

Then there's the music. Devo, Kate Bush, Peter Tosh, Doobie Brothers, Rickie Lee Jones, Talking Heads, Van Morrison, Bette Midler, Ornette Coleman, Eubie Blake and Gregory Hines. The Chieftains play inspired Irish folk music on the Margot Kidder show. Rick Nelson reprises his early pop hits. Frank Zappa is somewhat underwhelming, as he essentially gave up on his hosted show after dress rehearsal. The same goes for The Rolling Stones, who despite the hype, deliver a tepid, strained set.

The Blues Brothers naturally kill, backed by serious R&B studio veterans. But the most electric performance is delivered by The Grateful Dead, a band I never much cared for. On the first Buck Henry show, however, the Dead came alive, Jerry Garcia's stoned smile while playing through "Casey Jones" and "Good Lovin'" putting me at ease to enjoy the music. Of course, it could just be me getting older, a condition, if you've made it this far down the page, we now all share.