When I heard that Russ had died, I wasn't surprised. He battled diabetes, was at times in frail shape, and usually smoked when I saw him, which I'm sure didn't boost his health. He always seemed anxious, tense, pumping his leg up and down while sitting. Russ never appeared at peace. So the fact that he died relatively young didn't faze me. That he died four years ago and I recently found out

did throw me, however, like a delayed time wave slamming me into a wall.

An old mutual friend emailed me the news after I asked about Russ, whom I hadn't spoken to in over a decade. How is it that I didn't know this? As with much of his life, Russ' death was a secret -- at least to me. Back when I knew him, Russ would disappear for weeks at a time, leaving behind no word nor any trace of his whereabouts. Everyone assumed that he was hiding out in his parents' apartment, a huge place on the Upper East Side around the corner from Elaine's. He lived at home for the bulk of his life, occasionally spending time in his sister's apartment, or in another small apartment that his family owned. Russ was a native Manhattanite, and I knew few people as comfortable with the city as was he. In my early years there, Russ helped me adjust, that is, when he decided to appear publically. After every absence, Russ would suddenly pop up and act as if he saw you the night before. Whatever movie was playing in his head seemed strictly geared to him.

I can't remember exactly when or how we first met. It was around 1984-85, when I was living with my girlfriend Mary. I was writing for comics and performing improv wherever I could, while constantly trying to snag a spot on SNL or Letterman. I might have met Russ through an ex-Letterman writer I knew, which would make sense, since that writer was very old school when it came to comedy, the complete opposite of the Harvard Lampoon vets he worked with. Russ was old school, too, but he didn't live in that world like so many others I came to know through him. When he referenced Snub Pollard or Harry Langdon, he used their comedy as a springboard for his strange, contemporary bits. And anyone who knew Russ expected the odd, the bizarre, coming from him. Not in any off-putting or anti-social way -- Russ offered his perspective subtly. Sometimes it flew under everyone's radar, including mine. It isn't often that you meet someone as weird as yourself, though in many instances, Russ took it to places beyond my understanding. It wasn't an act, it was simply him.

In a sense, Russ was a lot like Joe Ancis, the off-stage legend who influenced Lenny Bruce and Rodney Dangerfield. Ancis rarely if ever performed due to serious stage fright. But he was reportedly the funniest guy at the bar, setting the tone for those younger comics who cribbed his style and outlook. I don't know if Russ directly influenced other comics. He was too idiosyncratic for that. He was fun to have around, especially late at night, whether in a club or a diner. Occasionally he would go onstage and join some improv game. But this didn't happen often. His humor wasn't meant to be shared via the traditional showbiz routes. There was a time, though, when Russ gave showbiz a serious shot.

He teamed up with two other comic actors, Paul and Jim, who were as different from Russ as they were from each other. Paul was a short-haired, muscular presence, resembling a college linebacker with the energy to match. Jim wore his hair in bangs, speaking quietly while slouching, as if he didn't want to get in your way. Mix in Russ, with his wide Irish face and pompadour, and you had The Poster Boys, one of the funniest anti-comedy teams I've ever seen, equally at home in experimental spaces downtown, or at Caroline's, venues the Boys regularly played.

They didn't perform sketches per se, nor delivered jokes as traditionally understood. They were always themselves, even while "in character." Sometimes their bits abruptly ended, no punch line or blackout gag in sight. The Poster Boys were absurdist, surreal, and very slapstick. Routines where two of them beat the third mercilessly usually made no linear sense, which made it extremely funny, since it was rarely connected to a set-up. Their verbal interplay was at once comic and casual -- seemingly rehearsed yet off the cuff. They worked hard on their act, polishing it to a point where it appeared thrown together at the last minute. This yanked the audience into their world, a scene much different than the standard comedy of that time.

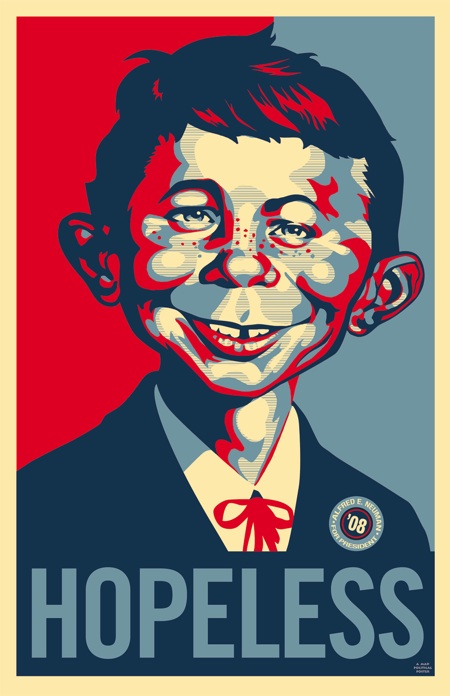

The Poster Boys came close to breaking through, but could never get over the top. What made them unique also limited them as they rose through the comedy ranks. They did a Barq's root beer commercial, which contained none of their humor but gave them national exposure. They hosted a Comedy Central July 4th marathon, performing quick bits between the commercials and endless stand-up specials. (My favorite was them shooting pedestrians from a rooftop, while Paul yelled down "Salute the flag!") They always seemed to have some TV deal in the works, but it never panned out. They performed at a theater in LA while working on a comedy pilot for Fox starring Rachel Sweet, a former teen singer for Stiff Records who moved into acting. I don't recall if that pilot was ever shot or considered for broadcast, but like so much else, that too faded away.

Once, while in Tom Schiller's apartment, I noticed a storyboard on his wall, with several Polaroid's of The Poster Boys tacked here and there. Apparently, Tom was going to direct them in a film called, "The Poster Boys Meet Frankenstein." When I later phoned Russ and asked why he didn't tell me about this project, given that I knew them and Tom, he replied in his typically Russ way: "I thought I did tell you. Huh. Well, now you know."

Sadly, the Boys never got to meet Frankenstein. Another project that fell to the wayside.

Russ and I professionally collaborated just once. A TV agent who liked my material got me a submission to Letterman. I had three weeks to deliver a comedy package. I was working alone at the time, and when Russ discovered that I had a shot to write for Letterman, he wanted in. I was reluctant, but convinced the agent to push us as a team. Problem was, Russ had no discipline as a writer, at least around me. His attention wandered, and sometimes he'd stare out the window, smoking a cigarette, while I was left wrestling with a premise. Whenever Russ contributed, he'd throw out the wildest ideas, some of which were extremely strange and hilarious, but not right for Letterman. I kept telling him this, but it made no difference. In the end, I wrote pretty much the entire submission myself, adding a few of Russ' sight gags which I made fit. Part of me felt used, and if we did get hired, how would Russ survive in those cutthroat offices at NBC? He'd be great to riff with, but I could see disaster if the head writer, at that time Steve O'Donnell (who now works for Jimmy Kimmel), expected him to sit down and write 30 Top Ten jokes on deadline. That wasn't how Russ operated. I'd probably have to cover for him, and that kinda pissed me off.

The opening on Letterman went instead to some Harvard guys. Go figure.

When I drifted out of comedy and into politics and media activism, I saw less and less of Russ, but we did stay in touch. After I got the editor-in-chief gig at New York Perspectives, Russ began phoning me with numerous suggestions, none of which I used. Again, he didn't understand the venue. Then he recommended a single mother he knew as a possible contributor. He had worked with her in an early comedy group he was in (Firing Squad, from which The Poster Boys emerged), and said that they were dating. I saw Firing Squad once, and didn't recall the woman he was talking about. But then, I was pretty loaded that night. So I replied, sure, send her stuff over. I'll take a look at it. If I hadn't done this, Russ would continue to call me until I relented. When her package arrived, I put it in a lower desk drawer, unopened. Yeah, like I was gonna feature some dimwit actress as a cultural commentator.

About a month later, one of my writers failed to deliver her copy, leaving me with a page of ads but no piece. Out of desperation I opened the package and read the actress's stuff. It wasn't bad. In fact, it was pretty fucking good, better than most of the material in that week's' issue. I phoned the woman, who was then living in Ohio, praised her piece and asked for more. Soon a regular, she moved back to New York where I fell in love with her. Naturally, she despised me from the beginning, which made me love her even more. She had every reason hate me, especially during that period of my life. Her perception was laser sharp, and it didn't hurt that she was gorgeous. I'll say this about Russ -- he did hang with some truly beautiful women. Funny guys usually do.

I actively courted this woman, breaking down her resistance with every scrap of charm I could find or pretend I had. It took awhile, as she was protective of her two-year-old daughter; but slowly, steadily, we became friends, then lovers, then I moved in with them. About a year after that, we married. Needless to say, this drove Russ over the edge. He believed that I stole the love of his life, and for a time he left hostile, sometimes threatening messages to me on our answering machine. That he and she broke up well before I made my move meant nothing. Whatever was left of our friendship ended then. I saw Russ once more, at a mutual friend's birthday party near Chinatown. By then I had a son and the "Mr. Mike" book deal, so my life seemed pretty solid. Russ recognized this and let down his guard. We exchanged a few pleasant, empty words while he puffed away on the building's front stoop. That was the last time I ever saw or spoke to him.

Russ is long gone now, and I feel a certain sadness. Part of it is about how our friendship ended. Part of it is imagining his final days, where there were amputations due to diabetes. Much of it is tied to those heady, creative days in our 20s, when comedy was everything, and I laughed harder and deeper than I ever did growing up in Indiana. Russ and I shared several recurring concepts, one of which was HeadProv, an improv group of actors sporting giant puppet heads. Sort of like The Residents meet The Groundlings. That never came to fruition, alas. Negotiating the stage while balancing a giant head

and improvising would be difficult for even the savviest talent. Still, what an image.

Russ left his mark on me. I'll never forget him.

THE WIFE: Shares her thoughts on Russ.